Technology, it seems, infiltrates all of our lives at a rapidly increasing rate. This is also true of bird conservation, as we often look to technology to ease difficulties encountered in field studies or long-term monitoring that we have been unable to overcome in any other way.

I am most familiar with the marine environment, so most of the examples I know are from that realm. But, with just a few moments of reflection, I am sure you could develop a similar list of examples of technology in conservation work no matter what ecosystem or avian taxon grabs your fancy.

Bird researchers, like other scientists, have long used specially designed tools to measure the minutia of specific aspects of the environment. But, with the advent of computers and particularly the recent, rapid miniaturization of that technology, we have seen nothing short of a revolution in the bird research and conservation world.

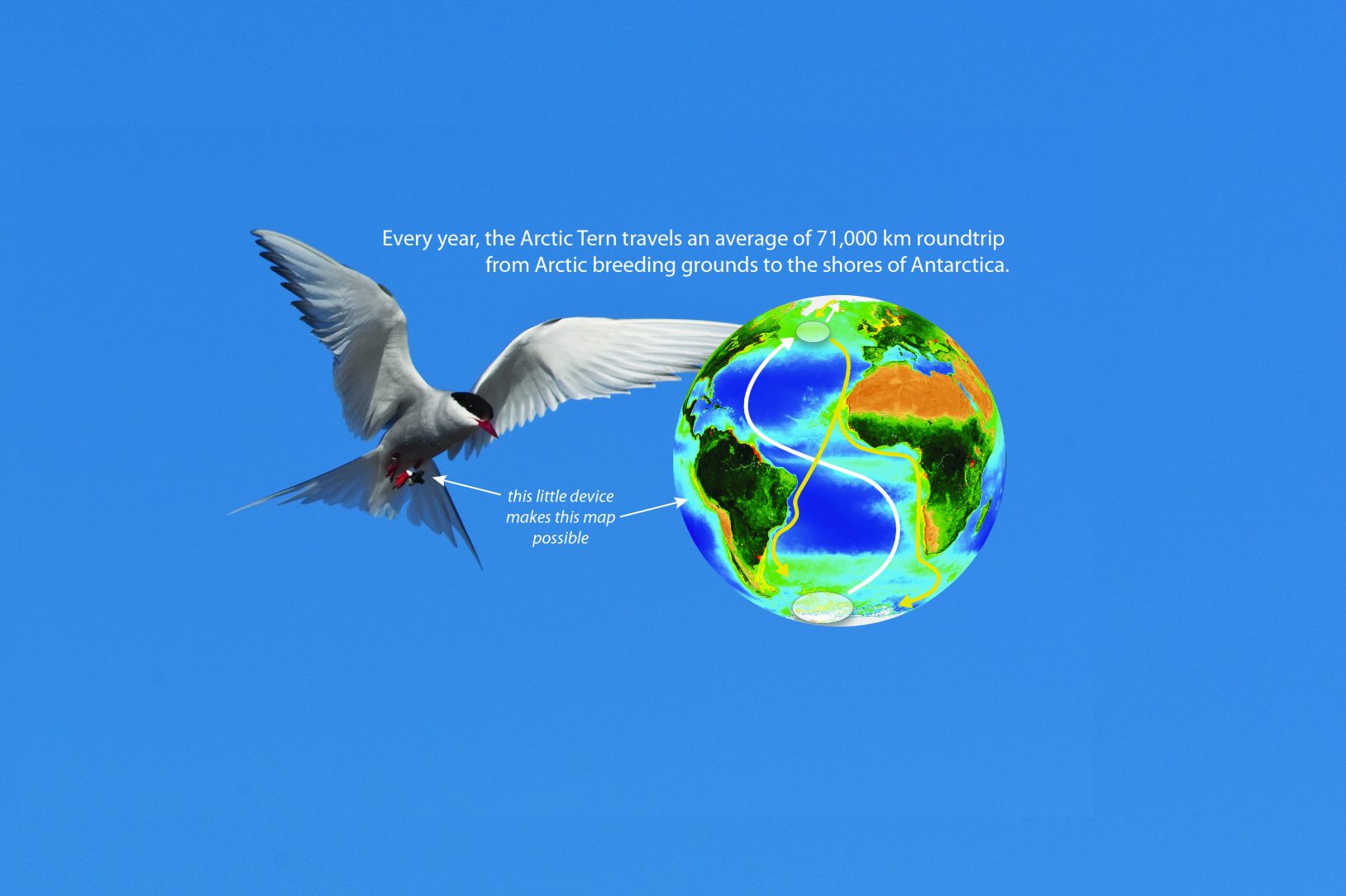

In the last few decades alone, tracking has expanded from the confines of extremely large species, like albatrosses carrying big, heavy battery-powered satellite transmitters to the daintiest of dickie birds carrying tiny data loggers to the ends of the earth and back again.

Tracking technologies are now widely used and varied, including the use of satellites, GPS, cellular networks, VHF tower arrays, and light-sensing geolocation. In place of batteries, solar cells allow the power of tracking to grow even more over space and time.

This is a revolution of unprecedented proportions, I believe, changing not only our understanding of avian capabilities and perceptions, but connecting the world in sometimes unexpected ways and redrawing the landscape of bird conservation opportunities.

In addition to technology for tracking and monitoring birds, digital cameras are being used in a number of innovative and enlightening ways. The improved quality and sensor capabilities of trail cameras, for example, have changed how we monitor species in the wild. Cameras can even be mounted on birds themselves, who then document their own behavior or interactions with prey, predators, or congeners throughout periods that could not otherwise be directly observed.

Similarly, birdcams stream the lives of a plethora of species directly to the desks of researchers and into the homes of bird lovers alike, 24/7. Using digital video or still cameras, we can fly offshore aerial surveys fly at altitudes of up to 2,000 feet, carrying out surveys without disturbing the species being counted and monitored. Thankfully, this also makes aerial surveys in the marine environment much safer!

For traditional boat-based surveys, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management recently developed a new offshore survey app, SeaScribe, which standardizes data collection and improve survey efficiency. Anyone with an Apple or Android tablet or phone can download that app for free from the usual app stores.

And, of course, there are drones. Increasingly, I see interesting accounts of constructive applications of drones to survey and monitoring projects that remove some physical barrier or improve efficiency in counting individuals in the most remote or otherwise difficult of terrains – from icy Antarctic cliffs to dense boreal forests.

With all of these innovative ways to collect critical information, it is an exciting time in bird conservation. With the efficiencies that these new research tools bring, hopefully, we will see more good news stories in bird conservation.

What could you do with these technologies to improve your reach?