To help the bird conservation community speak with a unified voice about common needs and themes, NABCI assembled the National Bird Conservation Priorities, which highlight 10 Priority Actions organized across 5 conservation themes. NABCI’s All-Bird Bulletin Blog will highlight projects and programs that work to achieve one or more of these Priority Actions. Today’s blog highlights an initiative that aligns with Research and Evaluation Priority Action: Develop multi-agency integrated approach to research and monitoring in order to provide information on broad patterns and trends.

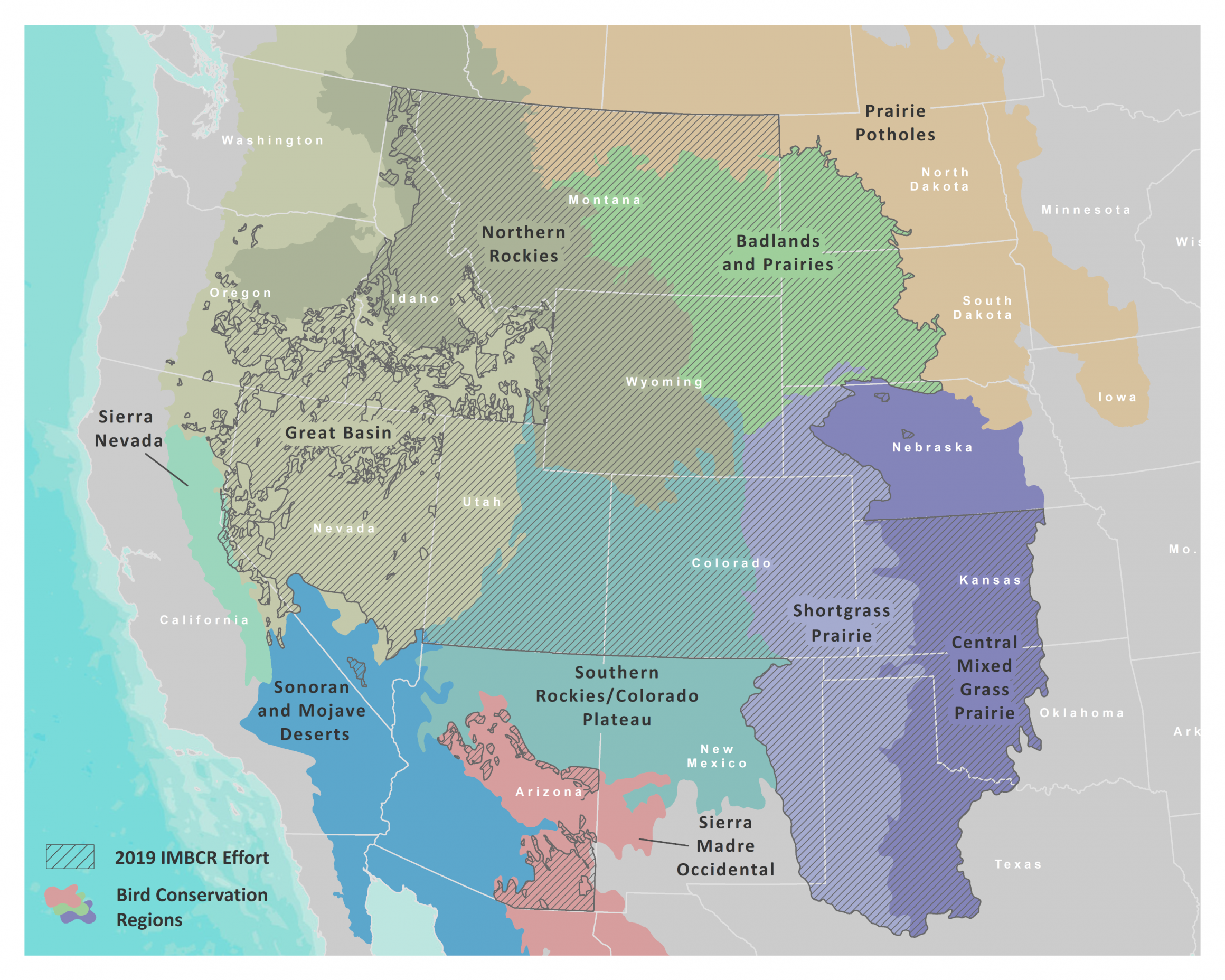

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act passed 100 years ago, and yet many avian populations across the U.S. continue to decline. The causes vary, but without monitoring we wouldn’t know if individual populations are increasing or decreasing or whether our conservation efforts are having the intended impact. Monitoring birds across large areas is a challenge, but it’s vital for making sound management and conservation decisions. The Integrated Monitoring in Bird Conservation Regions (IMBCR) program began in Colorado in 2008 with four partners—the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, and Bird Conservancy of the Rockies (then Rocky Mountain Bird Observatory). Over ten years later, IMBCR includes more than 30 partners and the geographic extent spans from the Great Plains to the Intermountain West.

NABCI recently released a document highlighting national bird conservation priorities and actions that should be taken to support healthy bird populations across North America. The IMBCR program is consistent with one of the priority action items under Theme 2, “Research and Evaluation,” which calls for a collaborative, integrative approach to research and monitor avian populations at large scales.

IMBCR is composed of governmental and non-governmental organizations in multiple states that each chip in to cover monitoring costs. Because everyone pools their monitoring resources, the monitoring footprint covers a larger geographic and temporal extent than if every organization conducted an individual effort. Monitoring also occurs over private and public lands and multiple jurisdictions, providing an all-lands approach and a more accurate picture of bird populations across the landscape.

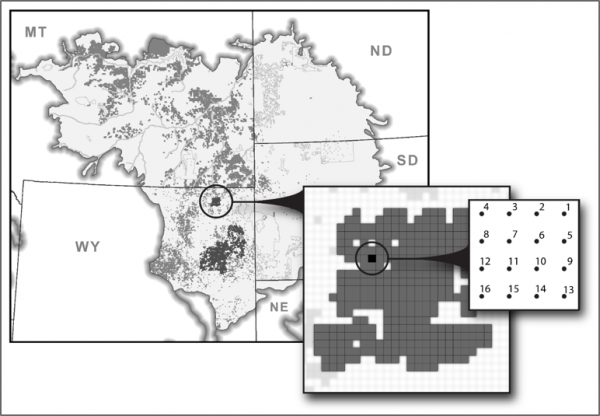

IMBCR was the first program in the nation to adopt a randomized, hierarchical approach to estimate bird abundance and occupancy across large regions. The sampling design starts with Bird Conservation Regions, which are split up into areas of inference for population estimates. In this way, population estimates are available at scales ranging from a single National Forest up to an entire state or Bird Conservation Region. Wildlife managers can also compare estimates within a management unit to the surrounding region to provide context and determine conservation responsibility for a local population. Density and occupancy estimates are available from the Rocky Mountain Avian Data Center for over 270 species at a variety of spatial scales including general survey locations, species counts, and sampling effort.

Example of sampling design for Thunder Basin National Grassland in the Badlands and Prairies Bird Conservation Region.

Having a rigorous sampling design and large partnership don’t mean much if the data are not put to use to influence decisions and actions. IMBCR data have been integrated into management and conservation practices at small and large scales for a variety of purposes:

- State-wide estimates provide information on Species of Greatest Conservation Need for state wildlife action plans;

- Habitat relationships inform bird response to management strategies such as grazing or natural disturbances such as fire and beetle kill;

- Targeted monitoring in project areas allows biologists to evaluate management actions or disturbances, such as ponderosa thinning or natural gas activity, and the impact on populations;

- Occurrence data and density estimates inform NEPA reports and other environmental assessments for project-level planning; and

- Trend estimates across time and space highlight populations in need of conservation measures or populations which have recovered.

The next ten years of monitoring for IMBCR should add to the existing effort of informing on-the-ground decisions that benefit birds and their habitats. If you are interested in more information on IMBCR, check out our website or 2017 publication. If you’re interested in requesting raw data or have other questions, contact Jen Timmer at Jennifer.timmer@birdconservancy.org.