To help the bird conservation community speak with a unified voice about common needs and themes, NABCI assembled the National Bird Conservation Priorities, which highlight 10 Priority Actions organized across 5 conservation themes. NABCI’s All-Bird Bulletin Blog will highlight projects and programs that work to achieve one or more of these Priority Actions. Today’s blog, originally published by the Pacific Birds Habitat Joint Venture, features the Pacific Golden-Plover’s annual migration between Hawaiʻi and Alaska, and aligns with four NABCI Priority Actions: Increase coordination and cooperation across federal agencies, and among federal and state agencies, to implement conservation policies and actions at broad scales; Develop multi-agency integrated approach to research and monitoring in order to provide information on broad patterns and trends; Recognize and address needs for species of concern in regional planning efforts, including Migratory Bird Joint Venture implementation plans, State Wildlife Action Plans, Canadian Bird Conservation Region strategies, and full life-cycle conservation business plans; Work with municipalities, corporations, and homeowners to support habitats for birds.

When the light lands just right on a Pacific Golden-Plover, you can understand how the English name is a perfect fit for this beautiful long-distance traveler. They are dotted with feathered flecks of gold that are especially brilliant against the black of their breeding plumage. There are two Golden-Plover species found within the Pacific Birds region, the Pacific Golden-Plover and the American Golden-Plover, strong look-alikes once thought to be the same species.

There is some range overlap of the two species during the breeding season, but they go separate ways during migration and spend the non-breeding season in different locations. American Golden-Plovers head south and east post-breeding, while the majority of Pacific Golden-Plovers head south and west out into the Pacific.

The scientific name, Pluvialis fulva, is derived from the Latin words pluvia–meaning rain or rain shower–and fulva, referring to the birdsʻ tawny or yellow color. There are at least two native names in Alaska, tuuliik (Yupʻik) and tullik (Inupiaq), both descriptive of the call. Hawaiians know the bird as kōlea. In Hawaiʻi during the non-breeding season, kōlea grace lawns and golf courses as well as more remote habitats. In late spring, they start to molt into their breeding plumage as they ready to head north–you may find them flocking together as they prepare for their journey.

For most of its stay in Hawaiʻi, the kōlea is in its non-breeding plumage. Jerry McFarland © Creative Commons

Range and Migration

Kōlea are highly migratory shorebirds. Globally, they breed in Alaska and Siberia and have a vast non-breeding and migratory range that includes not only continents and islands across the western Pacific, but India and eastern Africa. North America’s population breeds in Alaska and mostly overwinters (from our northern hemisphere perspective) in the Hawaiian Islands, Southeast Asia and Oceania–the islands that are dotted throughout the Southern and Central Pacific Ocean. While a small number can be found on the west coast of the U.S. in the non-breeding season, the birds that breed in Alaska primarily use the Central Pacific and East-Asian Australasian Flyways, making spectacular transoceanic flights to the non-breeding grounds.

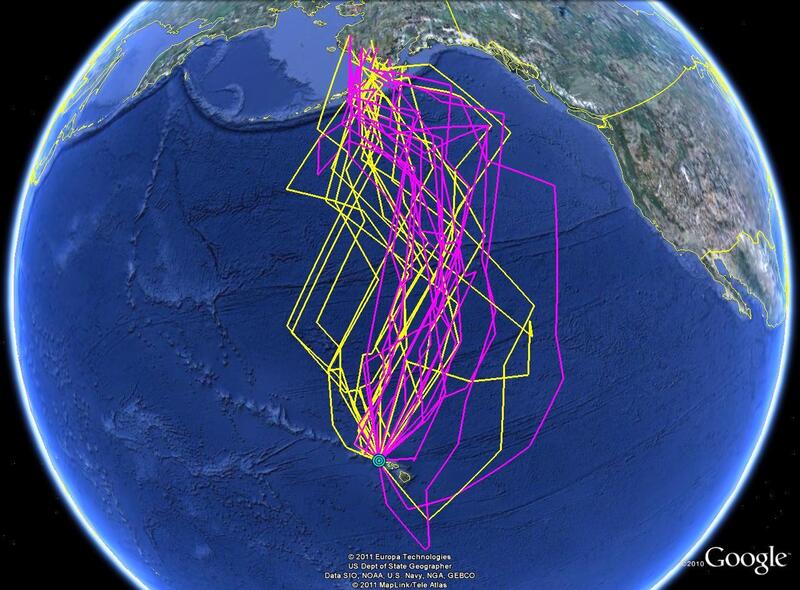

As studies have shown, there is a strong Hawaiʻi-Alaska migratory connection for a subset of the global population. These birds make non-stop, round-trip flights over the Pacific, covering 3,000 miles in just a few days. This Hawaiʻi-Alaska connection applies to the birds that summer in southern portion of the species’ distribution in Alaska, while the more northerly Alaska breeders migrate and overwinter throughout Oceania and East Asia. In Alaska, Pacific Golden-Plovers are mostly found in Bird Conservation Region 2, Western Alaska, though they may be seen elsewhere during migration.

The Alaska-Hawaiʻi Pacific Golden-Plover Connection. The yellow tracks show the path of geologger equipped birds traveling north in spring to nesting grounds, the purple shows the southward return in fall. Image by Dr. Oscar W. Johnson, used with permission.

Habits and Habitats

Starting in late April or early May, kolēa in Hawai’i will be starting off on their journey to Alaska’s arctic and subarctic tundra meadows where they will make nests, lay eggs, raise chicks, and take advantage of the abundant summer food supply of plants and insects.

The nest of these super-marathon migrants is a simple depression lined with mosses and lichens, often barely distinguishable from the surrounding tundra, at least to the human eye. Both parents will incubate a clutch of 4 small eggs. After their short but hopefully productive time in Alaska, the birds start their return journey as early as July.

The birds, especially the males, may return to the same area and even the same nest site year after year, a seemingly impossible feat of navigation when looking out across a vast tundra landscape. Similarly unimaginable, the birds may return to the same remote Pacific island upon return to the non-breeding grounds.

Conservation Status

According to the U.S. Pacific Islands Regional Shorebird Conservation Plan (2004), Pacific Golden-Plover is a species of High Conservation Concern, as it is in the 2019 Alaska Shorebird Conservation Plan. It is a Species of Greatest Conservation Need, as a Stewardship Species, in the 2015 Alaska State Wildlife Action Plan, and is a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Hawaiʻi’s State Wildlife Action Plan. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists it as a species of least conservation concern, but with a decreasing global population.

There are potential threats throughout the plovers’ global distribution, including habitat loss from sea level rise, major pollution events in marine or coastal environments, and a changing tundra landscape. As a group, shorebirds have seen precipitous declines over the past half century. The reasons are complex and not always clear, but habitat conservation and threat reduction are definitive steps we can all take to keep the plovers flying.

Get Involved

Participate in Hawaiʻi Audubon Society’s Kolea Count

Read More

From Birds of the World: Pacific Golden-Plover

From Annual Summary Compilation New or ongoing studies of Alaska shorebirds, December 2018: Migratory Movements of Pacific Golden-Plovers: GPS tracking and return rates

From Wader Study Group Bulletin:

- Tracking Pacific Golden-Plovers Pluvialis fulva: transoceanic migrations between non-breeding grounds in Kwajalein, Japan and Hawaii and breeding grounds in Alaska and Chukotka

- Tracking the migrations of Pacific Golden-Plovers (Pluvialis fulva) between Hawaii and Alaska: New Insight on flight performance, breeding ground destinations, and nesting from birds carrying light level geolocaters